Understanding The Anxious Generation

I came across The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt while researching early childhood development patterns- specifically trying to understand why so many educators, parents, and youth counselors are reporting heightened anxiety in children as young as 5 or 6, with the trend intensifying among adolescents and preteens. As someone who's 27 and straddling the line between millennials who grew up with the internet and Gen-Z who grew up in it, I have watched this unfold in real time. After reading this book, I walked away with a sharper understanding of how a technological shift quietly became a psychological one, and why what we casually call the “mental health crisis” among young people is less a crisis of character and more a crisis of design.

The Neurological Shift: How a Phone-Based Childhood Rewired an Entire Generation

The central thesis is what Haidt calls the Great Rewiring of Childhood- a fundamental restructuring of how children spend time, grow their minds, and form identities. Two simultaneous trends drove it:

Over-protection in the real world, and under-protection in the virtual one.

At some point, concerns about physical danger led to children being less able to explore without adult supervision. At the same time, age-appropriate guardrails for kids online felt like too much of a bother to design and implement at scale. So children were left free to wander through the wild west of the virtual world, where threats abounded. Walls were built in the wrong places.

The timing of this matters too. Early puberty is a period of rapid brain rewiring, second only to the first few years of life. After age 5, the brain begins selective pruning of neurons and synapses, keeping only the ones that have been frequently used. Activities that repeatedly activate certain neural pathways- especially if they’re rewarding- leave lasting structural changes in the brain. This is how cultural experiences literally change the brain, producing a young adult who is habitually in “discover” mode as opposed to “defend” mode.

Discover mode is your brain’s internal explorer- curious, open, risk-tolerant, ready to learn. Defend mode is the suspicious security guard- vigilant, threat-focused, pulling you toward safety and away from novelty. Play-based childhood is nature’s way of wiring up brains that tend toward “discover” mode. Phone-based childhood has shifted a generation of children toward “defend” mode, and it may be one of the most disastrous strategies we could have stumbled into.

But surely, kids are resilient, right? They can adapt to anything. Can't they?

The Misallocation of Protection: Children Are Anti-Fragile. We Forgot.

Kids actually are incredibly resilient- but not in the way we think. Haidt uses an analogy I can’t stop thinking about: children are anti-fragile. For example, the immune system is the ultimate anti-fragile system. It requires early exposure to dirt, parasites, and bacteria to configure itself correctly. Raise a child in sterile isolation and you harm them- you block the very mechanism designed to protect them later.

The same applies to emotional development. Children shielded from frustration, failure, and negative emotion don't emerge stronger. They emerge less equipped, because we've blocked the development of competence, self-control, frustration tolerance, and emotional self-management.

Now, some people might push back and say, “Don't children face challenges online? Can't they build resilience there?” In theory, sure. But here's the structural problem: when mistakes happen online, the stakes are never truly low.

In the real world, if you say something awkward at lunch, maybe 5 kids hear it. They might tease you for a day, maybe a week. Someone else does something embarrassing. Your awkward comment becomes ancient history. It's bounded by time, space, and memory. That's how the anti-fragile system is supposed to work- you make a small mistake, absorb the small consequence, adjust, and try again.

Online, the architecture is completely different. That same awkward moment can go viral. The timeline isn't a day or a week. It's indefinite. And because the mistake is public and permanent, the social cost isn't small and recoverable- it can feel catastrophic. Instead of a child gaining a sense of social mastery through trial and error, they walk away with a sense of social incompetence, lost status, and heightened anxiety about future interactions. The feedback isn't "try again differently". It's "never try again". The learning loop breaks.

And here's the evidence that this is actually happening: One of the most widely noted traits of young people today is that they're not doing as much of the risky stuff that teenagers used to do- less drinking, less drug use, less reckless driving, fewer teen pregnancies. At first glance, this looks like progress. But what if these changes came about not because this generation is getting wiser, but because they're withdrawing from the physical world? What if they're engaging in less risk-taking overall- healthy as well as unhealthy- and therefore learning less about how to manage risks in the real world?

In a nutshell: protective efforts have been misallocated. Completely. We removed low-stakes opportunities for children to build resilience in the real world, and replaced them with high-stakes environments online where mistakes carry consequences the developing brain isn't equipped to handle. Safety-ism has become an experience blocker.

So we understand the mechanism now. But what does this actually look like when it manifests in young people's lives?

What's Breaking Underneath?

Haidt identifies four ways phone-based childhood harms development: social deprivation, sleep deprivation, attention fragmentation, and addiction.

Attention fragmentation is the one I keep returning to. One of the primary developmental tasks of adolescence is building executive function- the ability to make a plan, resist distraction, and follow through. These skills are slow to develop because they're based in the frontal cortex, the last part of the brain to rewire during puberty. But here's the problem: staying in “discover” mode requires sustained attention. You can't explore deeply if you're constantly interrupted. Adolescents today are navigating the most attention-fragmenting devices ever engineered, at the exact developmental window when their brains are supposed to be building the capacity to focus. Every notification, every infinite scroll, every algorithmic rabbit hole trains the brain to seek off-ramps rather than stay on course.

Then there is addiction- specifically a concept called dysphoria, which is the opposite of euphoria. It refers to the flat, pervasive discomfort that many teens say they feel when they're separated from their phones and game consoles involuntarily. The brain, flooded with dopamine for sustained periods, down-regulates its own response. The user needs more stimulation to get the same effect. The brain enters a state of deficit in the absence of the stimulus. This is not a metaphorical addiction. It mirrors the neurological architecture of substance dependence. And when a brain is in withdrawal, it defaults to defend mode- anxious, threat-focused, unable to explore.

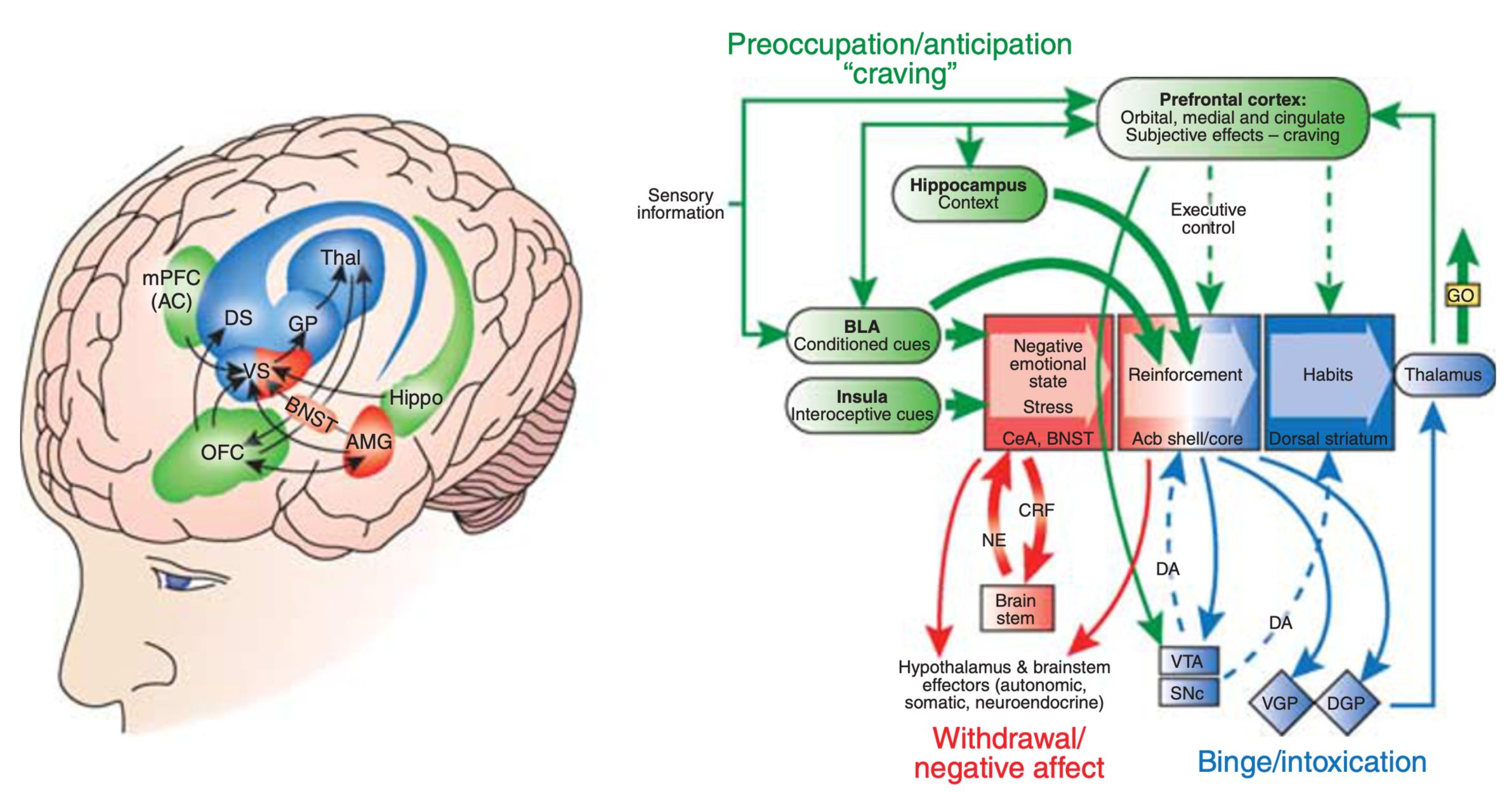

Source: Koob & Volkow, Neuropsychopharmacology (2010): This diagram shows the three stages of addiction and how they mirror what happens with phone-based compulsion. The binge/intoxication stage (blue) shows dopamine pathways from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) activating the nucleus accumbens- the brain's reward center- with each notification or scroll. The withdrawal/negative affect stage (red) shows the extended amygdala and stress systems (CeA, BNST) activating when the phone is removed- this is dysphoria. The preoccupation/craving stage (green) shows how the prefrontal cortex- the region responsible for executive control and still developing in adolescents- attempts to manage cravings but gets hijacked by the anticipation of the next dopamine hit.

Girls vs Boys: How the Algorithm Knows Which Buttons to Push

These complications don't affect everyone the same way. The patterns diverge sharply along gender lines- not because boys and girls are fundamentally different, but because their core vulnerabilities map onto different features of the digital landscape.

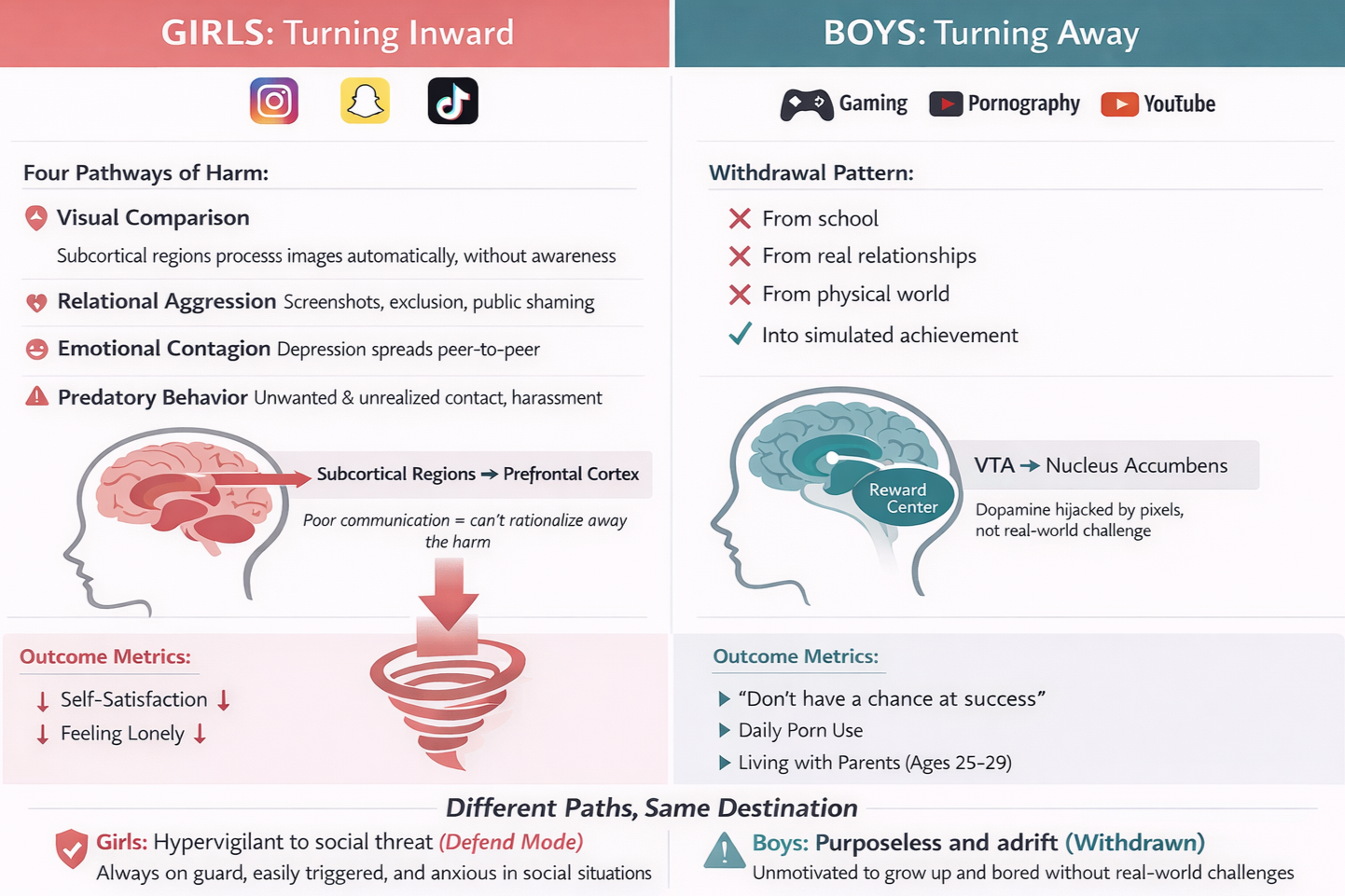

For girls, core vulnerabilities include a heightened drive for social connection, sensitivity to visual comparison, and the more indirect, relational nature of social aggression- which are all precisely exploited by social media's design. The visual comparison trap is particularly brutal: the comparisons happen in subcortical regions (automatic, emotional, pre-conscious), while the rational awareness that "this is just Instagram" lives in the prefrontal cortex. These regions don't communicate well during adolescence, which is why reminding a teenage girl that Instagram isn't reality is largely useless advice. The damage is happening below the level of conscious awareness. Additionally, social pain activates the same neural regions as physical pain- the anterior cingulate cortex lights up whether you're excluded from a group chat or physically hurt. For girls, whose brains are already primed for social connection through higher oxytocin sensitivity, social rejection on platforms designed for constant feedback creates a neurological loop of pain and compulsion. The result: girls increasingly stuck in “defend” mode, hypervigilant to social threat, unable to explore the world with curiosity or confidence.

For boys, the pattern looks different but the impact is no less serious. Where girls have turned inward with higher rates of depression and anxiety- boys have turned away. Away from school, away from real-world relationships, away from the discomfort and uncertainty of physical existence, and toward gaming, online communities, and pornography. These platforms deliver simulated versions of what their developing brains crave- agency, mastery, competition, connection- without requiring them to face the awkwardness and risk of real life. The problem is neurological: video games and pornography hijack the dopamine reward system in ways that make real-world achievements feel less rewarding by comparison. When you can experience the neuro-chemical reward of "winning" or sexual satisfaction without the effort, uncertainty, and delayed gratification of the real world, the brain down-regulates its motivation for real-world pursuit. We're seeing young men who feel purposeless, hollow, and adrift. At every level of education, from kindergarten through postgraduate degrees, girls are now outpacing boys academically. We're watching young men who never learned to launch, because the internet made it possible, for the first time in human history, to meet their needs without ever leaving their rooms- and the patterns are only intensifying for those coming up behind them.

Again, this is not to assign blame, but to understand the architecture of what is happening.

So, Where Do We Go From Here?

Haidt isn't nihilistic- and I'm not either. The internet is not the enemy. Access to information and tools that expand human capability is genuinely transformative and worth protecting. The problem is unfettered, unstructured, unsupervised access to social media platforms during the years when brains are most plastic and most easily shaped. When you talk to kids in school, what they say is that they don't want to miss anything, because if they miss anything, they'll be out of the loop, and if they're out of the loop, other kids will make fun of them for not understanding what's going on. Many parents don't want their children to have a phone-based childhood, but the environment has reconfigured itself so that any parent who resists faces a difficult choice: protect their child from the harms of early smartphone use, or protect them from social isolation.

We're trapped in a collective action problem. When there's ambiguity, people look to each other to see what everyone else is doing. Those cues help define the situation. The diffusion of digital technology into children's lives has been like smoke pouring into a room. We all see something strange is happening. We sense the effects. But when we look around and nobody's doing much about it, we stay seated. We assume that if it were truly dangerous, someone would have acted by now.

The most important thing I took from this book is that it's not too late to course-correct, but the window isn't infinite. Understanding the architecture of what happened is the first step toward changing it. Sometimes, the most radical thing you can do is simply stand up and say: I see the smoke too. Not because you have all the answers, but because breaking the silence gives others permission to act.